“We begin well if we start off with the heroic determination to be as impartial as we can in our attitude towards the actors in the great drama, to bear in mind and earnestly apply the excellent maxim “Put yourself in his place,” and to regard each and all of them not as men and women strangely habited and removed from us by the gap of century, but as friends with whom we may have come into contact in the chances of public, of social, of civil life. Once in this even and exemplary temper, we may with free minds turn our attention to the preliminaries of the great pieces”

Justin H. McCarthy The French Revolution Vol. 1 Second Chapter

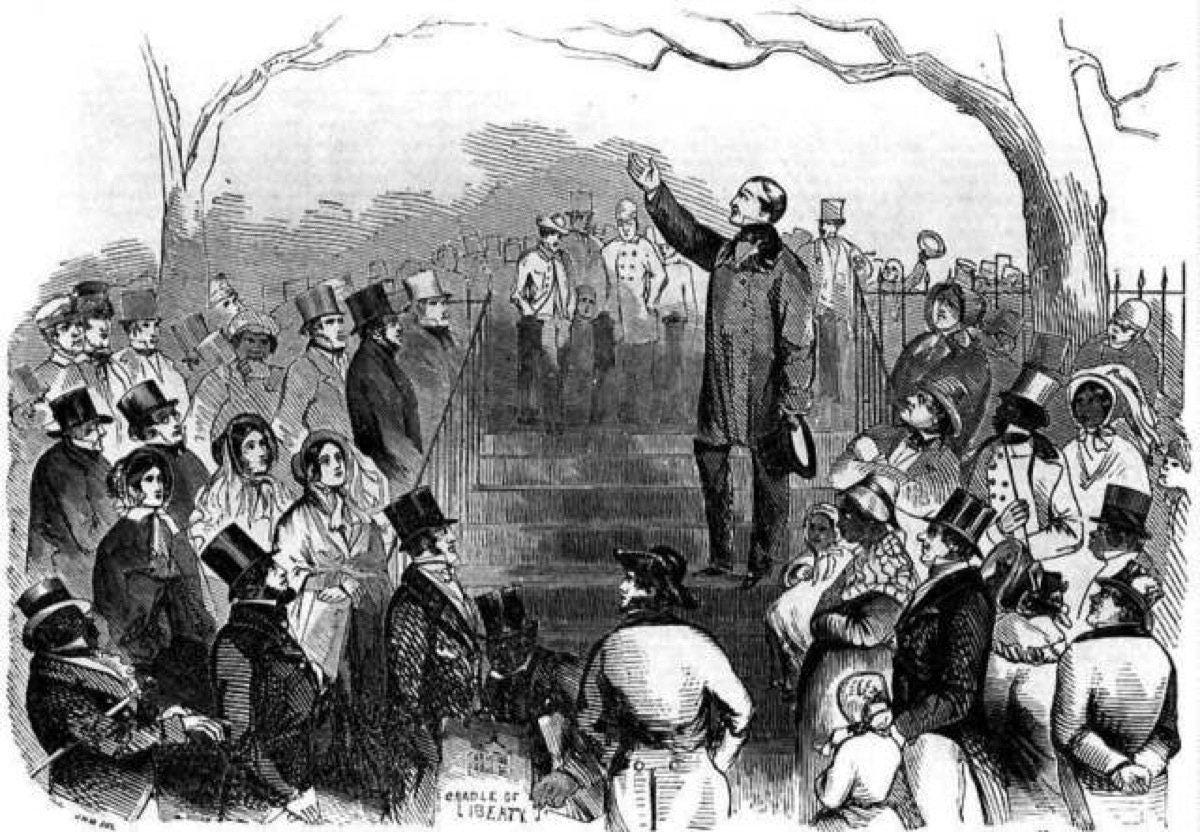

“No matter where you meet a dozen earnest men pledged to a new idea,--wherever you have met them, you have met the beginning of a revolution. Revolutions are not made: they come. A revolution is as natural a growth as an oak. It comes out of the past. Its foundations are laid far back. The child feels; he grows into a man, and thinks; another, perhaps, speaks, and the world acts out the thought. And this is the history of modern society. Men undervalue the Antislavery movement, because they imagine you can always put your finger on some illustrious moment in history, and say, here commenced the great change which has come over the nation. Not so. The beginning of great changes is like the rise of the Mississippi. A child must stoop and gather away the pebbles to find it. But soon it swells broader and broader, bears on it; ample bosom the navies of a mighty republic, fills the Gulf, and divides a continent.”

Wendell Philips, speech given to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society on January 8th, 1952

Introduction

Many have tried to put their finger on the illustrious moment in history when the fall of the Russian Empire began. In retrospect, things can appear inevitable. All previous trends are bent towards the known conclusion. Moments and individuals which at the time were felt to be of enormous importance are forgotten or relegated to bit roles in a drama whose central characters are all familiar to us. From the vantage point of history, regimes, and beliefs that at the time seemed immutable appear doomed and individuals toiling in obscurity, in the margins of the moment, are seen as destined.

If you told someone on the tricentennial of Romanov’s reign of Russia, that one of the world's oldest regimes would evaporate seemingly overnight and the royal family would be murdered in a nondescript basement, they would think you were a contrarian or congenital pessimist. Even more so, if you said that the regime will be succeeded by a small clique of radicals thought of at the time as crack pamphleteers and terrorists, then they might think you're mad. Lenin may have agreed with you. Months before the end of Czardom he told his comrades that he doubted they would live to see the revolution.

Over 100 years have passed since the 1917 Revolution, the epochal moment of the 20th century. Without it, the world would be unrecognizable. The global force of socialism, the rise of fascism, the Second World War, the Cold War that nearly ended life on earth as we know it, and the emergence of the United States as a hegemonic power. None of this could have occurred were it not for the whirlwind of unpredictable and unlikely events that took place in early 20th-century Russia.

Contained within the Russian Revolution are all the questions of modernity. The problems of philosophy, economics, aesthetics, and politics met in a collision that shook the world, and out of that wreckage emerged a regime the likes of which history had never seen. The Soviet Union was the largest and most radical political experiment ever attempted. At its peak, nearly three hundred million people lived in The Soviet Union, yet only a decade before the revolution, you could have fit nearly every major Russian communist in a Zurich cafe. Revolutionaries who had spent most of their lives in and out of exile and prisons, living without permanent addresses, under false names, surviving off of charity, meager book sales, and sometimes theft, ended up in the highest halls of power. By the same token, royals and aristocrats, who lived in palaces and country estates, surrounded by servants and ostentatious excess, who imported their clothes from France and nannies from England, who were placed by the grace of god on the top of the heap, died in exile or firing lines. Those left alive in the country were typically reduced to the legal status of former persons, imprisoned, and given lives of humiliation and deprivation. This project will try to gather away the pebbles and not present any supposed inflection point of history, but to tell the story of complexities and contradictions, of the impersonal forces and individual wills, the nightmares and triumphs of the fall of the Russian Empire and the revolutions that followed. It will focus on the lives and times of aristocrats and anarchists, royals and revolutionaries, reformist bureaucrats and radical terrorists, individuals whose names are immortalized in history, and those who are mostly forgotten.

We will try to get to the root of the oak tree that grew out of Russia. That from the point of view of today can seem inevitable but most certainly was not. We'll see how greatly the roles of contingency and chance play in history, how the past is never really past, hovering above us like a specter. We will also see the unbelievable ways in which small groups of people, sometimes even lone individuals, can appear at just the time and place to redirect the flow of history. The rise of socialism not only changed the shape and form of nations and the political landscape of nearly the entire world, it opened new understandings of what it means to be human, the horizons of the possible as well and the limitations of human attempts to decode the machinery of history and civilization. Certain events don’t occur but detonate, rendering the world unrecognizable and leaving a glow whose heat can be felt when all participants and witnesses are long dead. The history of revolutions is the history of groups believing that they have within them the power to dismantle and rebuild society. Most revolutions fail, but the ones that succeed reverberate for centuries in ways no one could foresee. As Marx wrote, “Men make their history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.”

This is a story of the Russian Revolutions.